Peacetime Promise: The Phoenix Project

Tension hovered in the cloudy skies over Michigan Stadium during halftime of an otherwise ordinary football Saturday in November 1958.

The marching band’s jackhammer entry from the tunnel at first had ushered in an upbeat atmosphere. But after assistant band director George R. Cavender led the band and the crowd in the national anthem – and following a John Philip Sousa tribute to commemorate Sousa’s 100th birthday – Band Director W. D. Revelli climbed onto his stand to lead the band in what began as one of its darkest but concluded as one its most profoundly delicate and powerful halftime shows ever.

The show was about the Phoenix Project – and the music began with a death march. Ominous. Haunting. Faster, faster … and faster still.

“Atoms have always been with us,” intoned Robert Trost, then-voice of the Michigan Marching Band. “Man, for 2000 years, has been attempting to harness them for his use. In the last fifty years, progress toward this end sped faster and faster. A host of discoveries piled knowledge upon knowledge [the played quietly, solemnly] until, in 1945….”

BOOM!

A canon fired, smoke rose, and the band scattered to turn from a field-sized atom into an atomic bomb’s mushroom cloud. One solitary band member, with a trumpet, played taps.

Another kind of boom

Ten years earlier, when the Phoenix Project did not yet have a name, a mission, or a building, students who had fought in WWII were pouring into Ann Arbor and enrolling at the University of Michigan, thanks to the benefits of the G.I. Bill. Of the approximately 18,000 students on campus at that time, 12,000 or so were veterans. They came to Ann Arbor with skills and experiences most tender-aged eighteen to twenty-somethings generally didn’t. They had felt the adrenaline of and seen the horrors of war. They had learned to put others first.

This also was an uncertain and unsettling time. It was difficult to know how the world would respond to the destruction the United States had unleashed when it dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. These U-M students brought with them a special problem, and a special hope.

In that spirit, the student legislature and student body, convinced the U-M Regents that a “mound of stone,” however beautiful, was not enough to honor those Michigan students and faculty who lost their lives in WWII. They would go to every student, every alumnus, and raise the money necessary to create a functional memorial. It didn’t yet have a name, or a shape, or function, but the starting point and direction were set.

Upon the recommendation of then U-M President Alexander Ruthven, the Board of Regents unanimously approved this yet-to-be-named project, and a war memorial committee was formed. It included Dean of Students Erich A. Walter as chair, faculty members Robert C. Angell and William Haber, Regent Roscoe Bonisteel, U-M administrator Marvin Niehuss, and three students who were also veterans of WWII – Arthur DerDerian, Arthur Rude, and E. Virginia Smith. Smith (’50, LSA), served as a nurse in the Pacific theater; DerDerian (’45-’48) served as an aviation cadet; Rude (’42, LSA; ’49, LL.B.) served as a first lieutenant in the Army.

Walter went to New York to meet with alumni, including a friend of his, Fred Smith, who was described in the May 17, 1948, issue of the Michigan Daily as “a tall, greying 39-year old New York publishing executive” at Book-of-the-Month Club. After their meeting, Fred Smith, no stranger to sales or wordsmithing, wrote his proposal for the memorial. Smith envisioned something big and beautiful, something befitting a half-time marching band show – and then some.

“As vital to the future of mankind as the continuation of religion; and the devotion of the people involved in it should be no less unstinted,” Smith wrote. The committee, regents, student legislature loved the idea – not only the concept but also the name Smith had suggested: The Phoenix Project.

Wrote Walter: “We have named the memorial The Phoenix Project because the whole concept is one of giving birth to a new enlightenment, a conversion of ashes into life and beauty.”

The Phoenix Project, as Smith and the committee visualized it, would consist of an “academy of scholars recruited from this and other universities … [who] would devote their full creative powers to the task of converting atomic energy to peace-time purposes and of utilizing it for the benefit of mankind.”

Phoenix rises

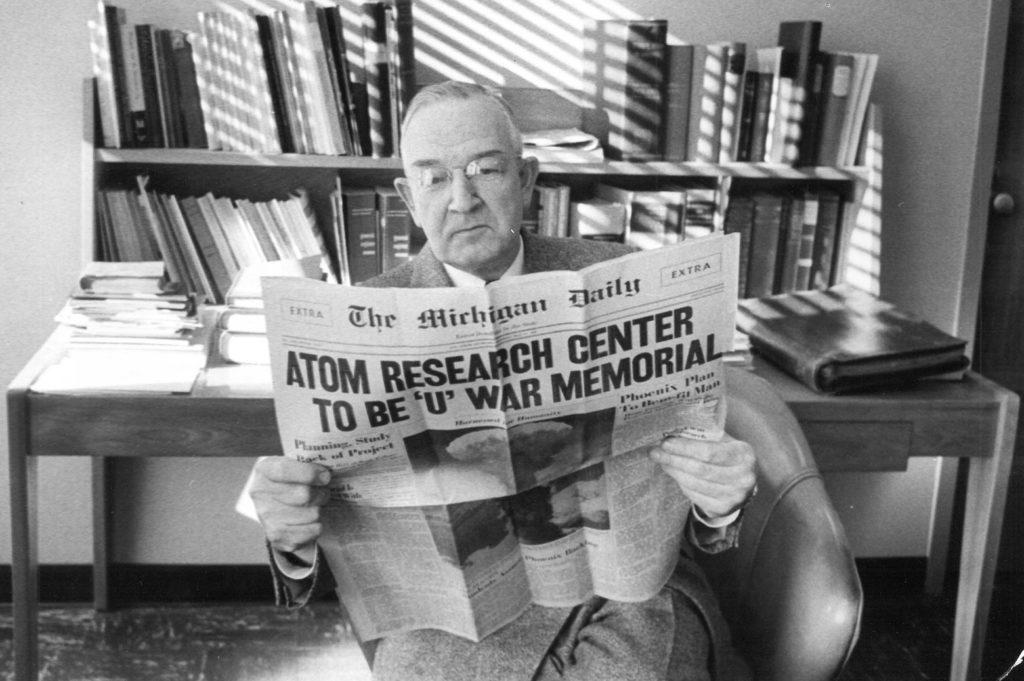

On May 1, 1948, the Regents gave their unanimous approval. On May 17, 1948, The Michigan Daily published a special edition, announcing the project to the student body, and asking for their help in raising funds. The front page, four columns wide, was a mushroom cloud. “Pictured above is the awesome smoke column towering more than 20,000 feet high above Nagasaki Aug. 10, 1945,” the caption read. “This same tremendous energy will be harnessed by the Phoenix Project to aid, rather than destroy, civilization.”

On page two, and spilling onto page three of this same edition, were the names of the 474 war dead. (The list later grew to 579.)

“I don’t see how students can help catching the fire when they think it out, and their enthusiasm is vital in selling it to Americans and the world,” E. Virginia Smith told the Daily.

Arthur Rude was quoted, too. “The students themselves must be the publicity agents for the Phoenix Project. That is their biggest single job.”

DerDerian, who planned the first, albeit modest, fundraiser – a raffle at the 1947 J-Hop dance – said, “If the students get a spirit on campus of what the Phoenix Project can someday mean to mankind, it will be felt throughout the entire world.”

In all, approximately 1500 students volunteered to participate in the drive.

The students themselves must be the publicity agents for the Phoenix Project. That is their biggest single job.

President Alexander Ruthven called The Phoenix Project “the most important undertaking in our University’s history.”

“It is important to recognize just how bold this effort was,” wrote former U-M president and dean emeritus of Michigan Engineering James Duderstadt. “At the time, the program’s goals sounded highly idealistic. Atomic energy was under government monopoly, and appeared to be an extremely dangerous force with which to work on a college campus. This was the first university attempt in the world to explore the peaceful uses of atomic energy, at a time when much of the technology was still highly classified.”

The Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project was a phoenix-like project in that it harnessed U-M’s students’ emotions, intellect, and patriotism into a project for peace. The University of Michigan students became the phoenix – the new, young “birds” who rise from the ashes of WWII, live another life cycle, and soar like eagles, in this case, with maize and blue plumes.

Phoenix firsts

The Phoenix Project also was the University’s first fundraising campaign. All the funds came from students, alumni, family, and friends (corporate and otherwise). The campaign raised $7.3 million (almost $64 million in 2014 dollars) by the time it ended in 1953. It also grew the University’s physical footprint, and was the first set of laboratories built on the new North Campus.

Over the years, Phoenix Project funds supported hundreds of peacetime atomic energy-related projects that garnered national and international attention, including a Nobel Prize-winning discovery – Donald Glaser’s liquid bubble chamber, which made possible rapid, easily interpreted photographs of rare atomic interactions.

A new reactor and a new department

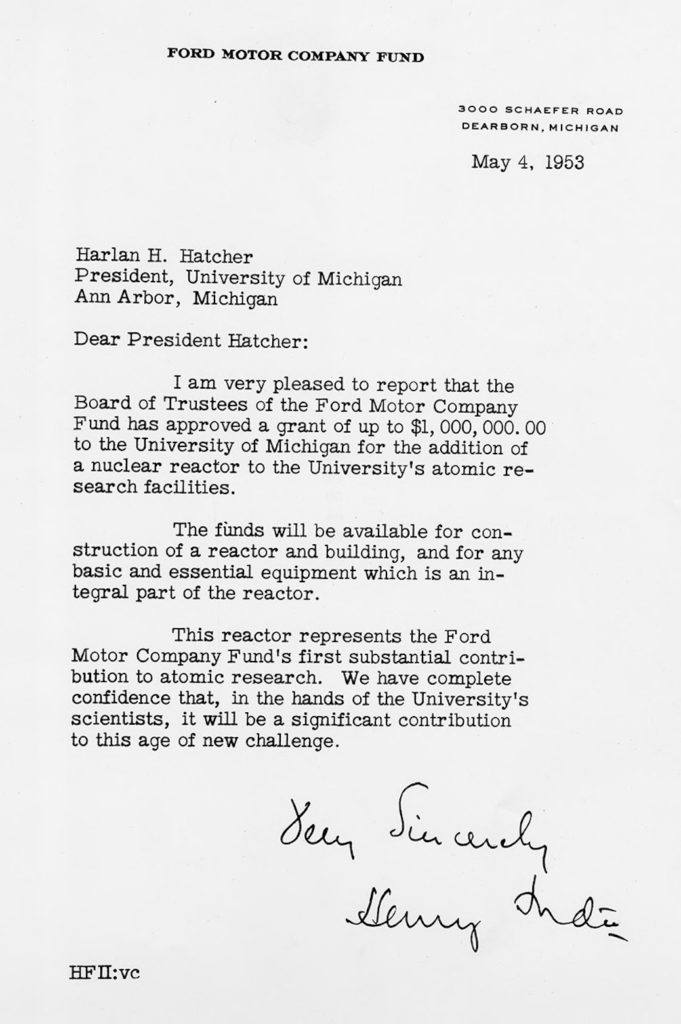

The Ford Nuclear Reactor (built with a $1 million donation from the Ford Motor Company) was dedicated in November 1956 and achieved criticality in September 1957.

In 1958, the Department of Nuclear Engineering was formed (with Henry Gomberg, who also would become the second director of the Phoenix Project, as its first chair) to offer graduate degrees, and the department used the facilities of the Phoenix Laboratory and Ford Nuclear Reactor. In 1995, the department was renamed Nuclear Engineering & Radiological Sciences.

The nuclear reactor was the Phoenix Project’s centerpiece, and produced several isotopes – for the medical school, and for the auto companies—and it offered neutron- and gamma-radiation damage testing services. (The reactor was decommissioned in 2003.) At that time, the MMPP was transferred to the Energy Institute. The building that housed the FNR was renovated and reopened as the Nuclear Engineering Laboratory (NEL) in 2017. The new equipment in the new lab included a high-resolution system for imaging coolant flow in reactors in unprecedented detail and an accelerator to aid in the development of faster, more accurate ways to identify nuclear materials. In 2021, the Energy Institute was disbanded and NERS regained proprietorship.

In April 2019, the department launched the Fastest Path to Zero Initiative, with the mission of identifying, innovating, and pursuing the fastest path to zero emissions by optimizing clean energy deployment through energy innovation, interdisciplinary analysis, and evidence-driven approaches to community engagement. The Fastest Path offices are housed within the MMPP.

Back to the beginning

“As in ancient mythology,” continued Michigan Marching Band announcer Trost on that overcast afternoon in 1958, “when the Phoenix bird was born out of his ashes, so at Michigan, The Phoenix Project for the constructive use of the atom was born from the ashes of Bikini, Nagasaki, and Hiroshima.

Over the years, Phoenix Project funds supported hundreds of peacetime atomic energy related projects that garnered national and international attention.

The band broke from the shape of a mushroom cloud into a free piston, and into a man, symbolizing nuclear energy’s relationship and contribution to humanity and medicine. The band then took their positions to form the shape of a phoenix.

“By its name and in its dedication, who gave their lives for peace, The Michigan Memorial Phoenix project is truly like the legendary phoenix bird of Egypt.

“For those consumed by the fire of war, live revitalized in its symbol. In performing its peaceful functions of using the atom for instruction, research and service to education and industry, the Phoenix Project has been able to carry on 185 projects during the last 10 years. With its seven campus laboratories, including the Ford Reactor, with its faculty and students, with interest from important people throughout the nation and from all over the world, the Phoenix Project stands as one of the largest and finest education programs for the peaceful use of atomic energy. Those associated with the Phoenix Project can be proud of its 10 years of peaceful achievements, and long may it continue in memory of those to whom it is dedicated – and for the betterment of all mankind.”

By Jan Schlain

Updated by Sara Norman