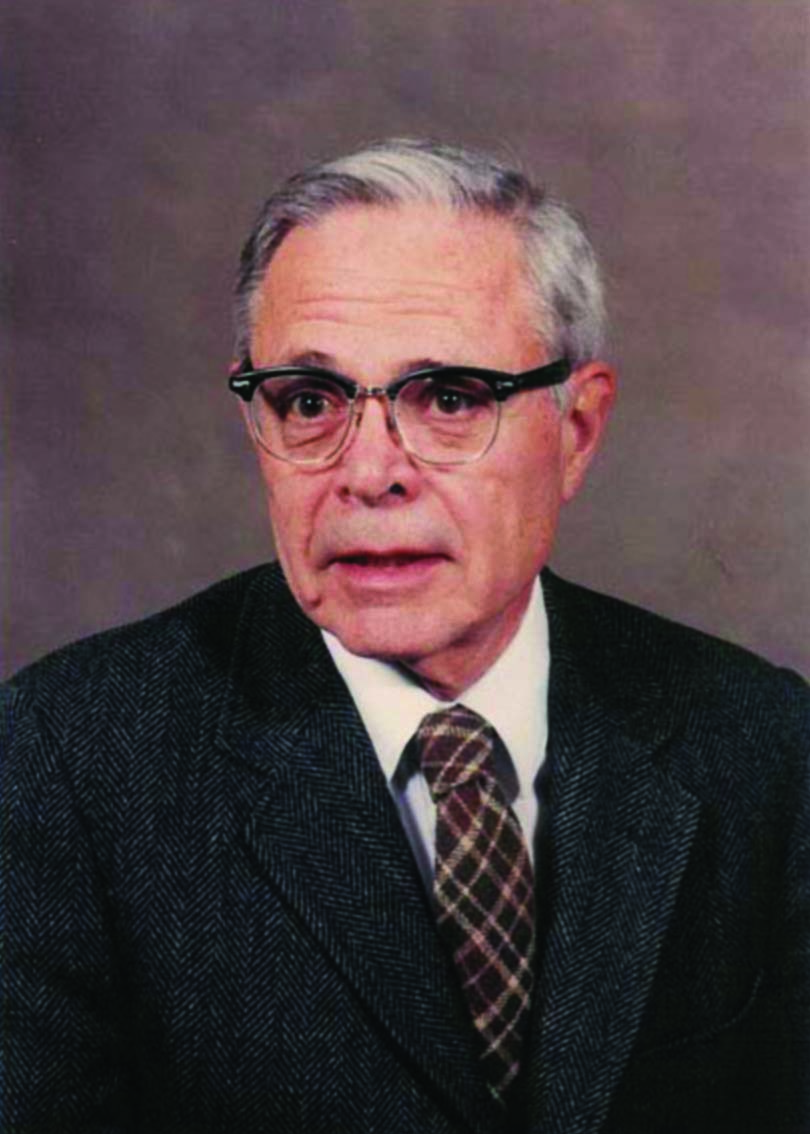

To my childhood ear, the Beemo Floor was as familiar a name as any among the words that identified our daily household world. “Dad’s at work tonight at the Beemo Floor,” my mother would say. Or Dad would tell us he had to race off to check the machine on the Beemo Floor. “My Dad’s not home right now, he’s at the Beemo Floor,” I explained to callers on the phone. As all children do with words they first possess as sounds in the mouth, one day I suddenly parsed it out, beam hole floor, and this came as a shock. It was an epiphany as much in the lexical realm as the imaginative one. If it had turned out to be the “be more floor” I could not have been more astonished.

But this epiphany was greatly surpassed by a second, when later my father took me with him on the first of many visits to the laboratory on the beam hole floor. The beam hole floor was the default name given to the basement pool-bottom level of the Ford Reactor at the UM Department of Nuclear Engineering Phoenix Lab, where scientists and students from all over the world worked an ever-changing array of experiments set up around the reactor perimeter like a necklace. To enter it, you had to pass through a double-doored chamber (like C. S. Lewis’s wardrobe door to another world) that read your body radiation level, and then read it again when you left. Once inside, you stepped into an underground city of beeping and purring machinery, spectrometers, targets, detectors, shields, counters and computers, divided into shantytown neighborhoods by makeshift masonite and boron barriers to isolate one experiment from another. What does a father say to his daughter by way of a tour of such a place? “We are looking at the inside structure of a crystal by bouncing neutrons off it and capturing the scatter pattern. You can just see the target crystal in there, surrounded by detector panels. There’s the hole where the neutron beam emerges from the reactor, and we’ve placed the crystal at just the angle…” And it hit me. For although I had understood that “beam” and “hole” were individual words, the idea of a hole with a beam coming out of it just hadn’t taken hold. My world turned. A hole with a beam coming out of it!

In my mind’s eye, the beam hole is not much more than a little hole in the wall, maybe 1/2 inch in diameter, a couple of feet up from the floor. Am I remembering the actual hole, or my amazement at its availability to naked sight, its… dumb presence? Like a cartoon knothole in the wall you could look through. “But Dad, I don’t see the beam!” “Ah… it’s invisible, you can’t see it.”

With this invisible beam, we look into the subatomic space inside a crystal. With my Dad’s voice still in my ear, the beam hole occupies a central place among the great counterintuitive mysteries of the world.

Elizabeth King